|

| Louise Bourgeois |

|

| Maman, 1999 Louise Bourgeois A sculpture at the Guggenheim that was installed after the Guerrilla Girls advocated for Louise's inclusion at the museum. |

Louise’s childhood was littered with memories of her father casually having sexual relationships with any woman he wanted and that her mother would turn a blind eye to the fact that one of his mistresses was actually “residing with[in] the Bourgeois family” (TheArtStory, 2013). This, of course, was extremely influential in almost every one of Louise’s paintings and sculptures, drawing inspiration from “her relationship with her parents and the role sexuality played in her early family life” (PBS, 2012). The emotionally scaring nature of her father’s actions and mother’s intentional ignorance left Louise angry and confused and caused her to channel her artistic abilities into producing art that discussed the ideas of “traumas…the feminine psyche…beauty…sexual desire and confusion” (TheArtStory, 2013). Louise’s art, which reflects her childhood experiences, isn’t only representative of her feelings towards her father and what he did; it is a survey of the male’s role in society and her critique of masculinity and power.

|

| Seven In Bed, 2001 Louise Bourgeois |

|

| Couple, 2004 Louise Bourgeois |

|

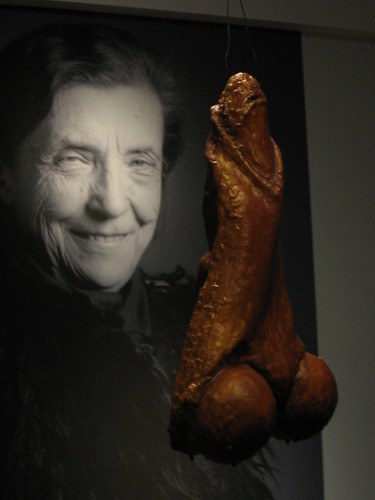

| Fillette, 1968 Louise Bourgeois |

|

| Les Mains/The Welcoming Hands, 1996 Louise Bourgeois |

Louise Bourgeois’ work, although it is quite obvious now, was “recognized only in retrospect…as a metaphor for gender (in politics and society)” (Chadwick, 324). Yes, there is the possibility that her some of her pieces may only be sentimentally significant to her and that they might not have been created with the intent to stir up a debate- but the situations depicted her sculptures were so relatable to other women in society that Louise managed to pave the way for other courageous female artists to follow suit. Louise’s art not only challenged the standard of art in the 20th century, but it still manages to stand out even to this day. Not many females have ever sculpted and displayed as vivid of a phallus prior to Louise and I doubt that anyone in today's society would have the “balls” to do it today. Louise Bourgeois has not only managed to successfully tell story of her own life through her sculptures, but she has told the stories of many other women too- standing as a pinnacle of feminine strength within a society still largely dominated by men.

Works Cited

art21. "Louise Bourgeois." PBS, 2012. Web.

<http://www.pbs.org/art21/artists/louise-bourgeois>.

The Art Story. "Louise Bourgeois." The Art Story Foundation, 2013. Web. <http://www.theartstory.org/artist-bourgeois-louise.htm>.

Crone, Rainer, and Petrus G. Schaesbe. Louise Bourgeois: The Secret of the Cells. Prestel, 1998. Print.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. 4th. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2007. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment