Overall, our group focused on movements and pieces that showed a transition from the archetypal view of the female to a variety of points of view in each movement during the early 20th century. Some of these movements included Expression, Surrealism, and Abstract Modernism

Neil

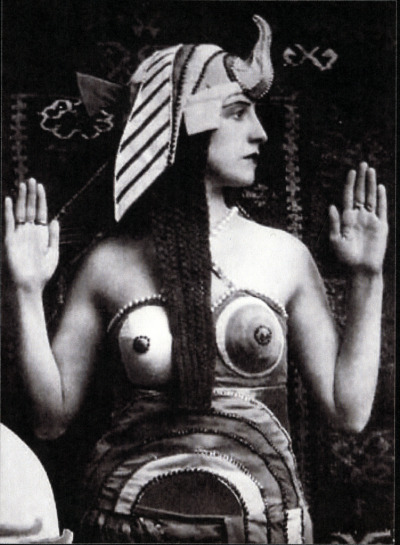

My main focus was on two artists that in their own ways tackled female sexuality. Both Suzanne Avadon and Paula Modersohn-Becker tackled the concept of the male gaze in their own ways. Both had a focus on the female nude. Avadon took the poses and actions that were typical in Western Art and took a more realistic approach. She put her models in awkward positions and in settings more ideal to society instead in a grand background that emphasizes the female. Modersohn-Becker took a much more abstract approach and simplified her models in both foreground and background. She also placed her models in positions not typical of the past works. In both cases, the definition of the male gaze is in question. Are their pieces supposed to be for the pleasure of man, or is there more of a woman's right movement concept taking the forefront?

|

| Paula Modersohn-Becker's "Self Portrait with Amber Necklace" 1906 |

|

| Suzanne Valadon's "The Blue Room" 1923 |

These two artists, Leonara Carrington, and Frida Kahlo are both Surrealist and considered Mexican influential artists. The surrealist movement is a art and literary movement that stresses the significance of letting one;s imagination rule, minimizing the use of logics. It is also a cultural movement that started in the early 1920's. The surrealist movement becomes the focus for a dialogue which is viewed as the revolutionary tool that would overthrow the control exerted by the conscious mind. (Chadwick, pg. 314) It is also considered a revolutionary movement, which also has affect on the arts, philosophy, social theory, film, and literature.

|

| Lenora Carrington's "Self-Portrait" |

|

| Frida Kahol's "The Broken Column" |

Margaret

The artists that I chose to speak about on a personal level are iconic in their century and location have a resonating impact in my eyes. Kathe Kollwitz emphasized her form of German Expressionism by focusing on the social conditions during the Prussian Empire. She divorced herself from the modernist movement a bit because although artistic freedom occurred she wanted the impact to be emotional and political to show the truth about Women of the early 20th century. Romain Brooks set the iconic fashion and archetype--persay--for the early 20th Century lesbian. The way she expressed her own self portrait represents that through painting it can set not just a new trend but a voice for another community that breaks the societal norms of gender roles.

|

| Kollwitz's "Portrait with Hand on Brow" |

|

| Romanie Brooks' "Self Portrait" |

Tehreem

I discuss two artists, Gwen John and Georgia O'Keeffe. Gwen was basically a non-joiner so she couldn't be counted as a part of the Modernist movement were it not for a few elements from the movement artists in her work. She loved repetition and painted many versions of some paintings. She was overshadowed by her brother, Augustus John who was a popular painter of his time. Gwen's paintings were usually very closely toned. Georgia was much more outspoken and came to be much more famous as an artist in the U.S. Her art was usually much more intense and had technical attributes such as her use of different spaces. She faced much criticism and was often misunderstood but she still persisted and continued painting till old age.

+Wide-Awake+Tortoiseshell+Cat.jpg) |

| Gwen John's "Wide Awake Tortoise Shell Cat" |

|

| Georgia O'Keefe's "The American Marathon Building" |

.jpg)