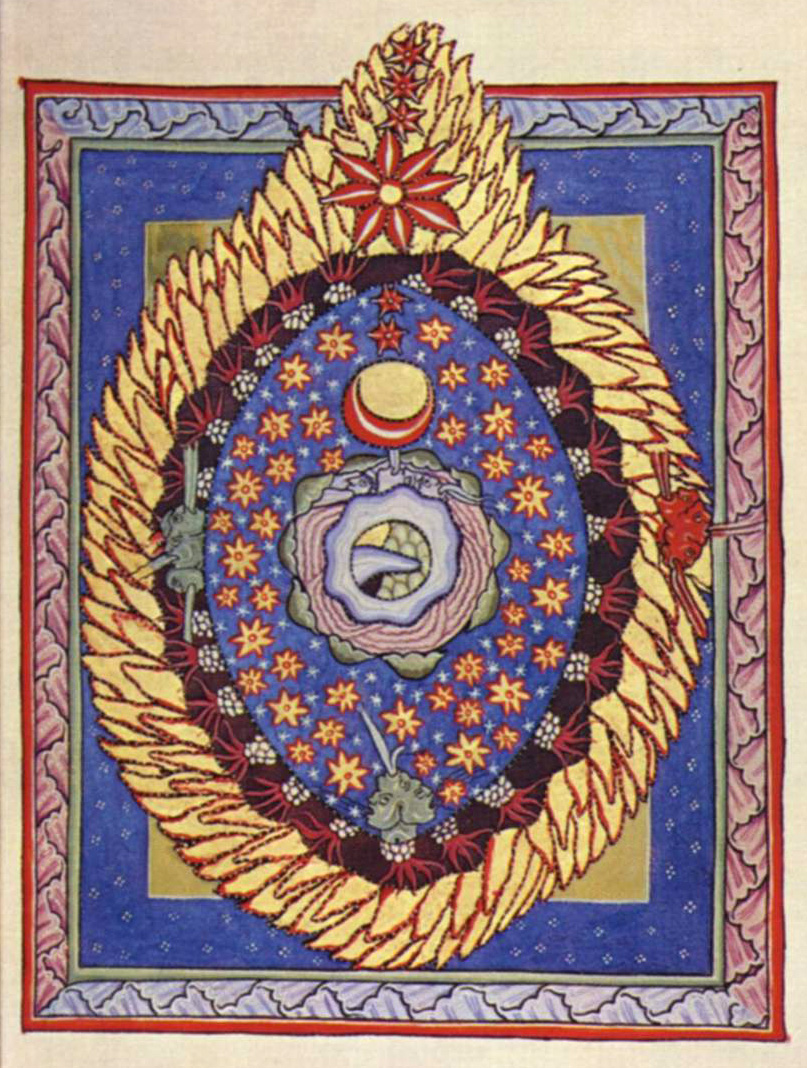

The history of Western art begins with the classics, but documented evidence of women artists is sited in later centuries, beginning with the Middle Ages. Art was at this time directed by the Catholic Church and society as a whole was rigidly divided under the principles of feudalism. Artists were commissioned by abbots, abbesses, kings and nobles; many of these commissioned artists were women (whose work was credited to the patrons and thus lost to the ages). In Ottonian Germany, women artists either worked in the family business or escaped the life of a domestic housewife by living as nuns in convents. These women were fortunate, for “even as the status of women was beginning to decline in other parts of Europe…great convents continued to flourish as places of learning in Germany” (Chadwick, 49). One of the most memorable women from this region was Hildegard Von Bingen, a nun whose work demonstrated the popular medieval theme of the human body as a vessel. Von Bingen believed God’s will was translated to her in the form of visions, which she later recorded in her first book, Scivias. Her work “[integrated] all aspects of life…presenting female authority as a restitution of the natural order, not a threat or challenge to it” (Chadwick 62). She believed feminine qualities of chastity and obedience would restore the Church to its former glory. She claimed that this was God’s will, not her own. Von Bingen urged Christians to live a more spiritual life, lamenting the corruption of the Church in Scivias: “I conceive many who tire and oppress me, their mother, with their various…heresies and schisms and useless battles” (Guerrilla Girls, 25). This is, of course, not only a vision of the many brutalities committed by the Catholic Church, but a vision of her place as dictated by the Church; her place as a woman, as a creature inferior to men.

|

| Hildegarde von Bingen, Scivias, 1142-52 |

From the Middle Ages comes the Renaissance, notable for its profound socioeconomic changes. The shift from feudalism to mercantilism (the stirrings of capitalism) at this time generated greater wealth amongst the people—and with the decline of feudalism, of course, came the decline of the Church. Art was thus commissioned by larger sums of people; Renaissance art overall displayed a greater appreciation for secularism and rational thinking. Gender divisions were also solidified at this time: The public sphere became more important, and with it the role of men. Arts and crafts were separated into two distinct entities, and women were assigned to the latter: the “inferior” craft of embroidery and lace-making. Nevertheless, there were select women who dared to defy these social conventions: Sofonisba Anguissola and Artemisia Getileschi were two among them. Anguissola in particular "opened up the possibility of painting to women as a socially acceptable convention" (Chadwick 77). She worked for years at the Spanish court and thrived during the Renaissance. Her most notable paintings are her own self-portraits, in which she, unlike other women in paintings at the time, stares directly at the spectator as if to assert her own self-possession. Getileschi's case presents a similar theme of defiance, particularly in her take on "Susanna and the Elders," which must necessarily be contrasted with Tintoretto's 1556 version.

,_Artemisia_Gentileschi.jpg) |

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Elders, 1610 |

The latter version seems to be inviting the spectator to look at her, removing the elders from blame with the addition of the mirror. Fast forward to the 1610 version by Artemisia Getileschi: Susanna is clearly distressed. The elders are being demonized, and rightly so. The woman is not on display, which is not what can be said for the majority of Renaissance paintings.

The 17th and 18th centuries saw a shift from the adoration of reason and mathematical precision to a greater appreciation for genre paintings. Paintings at this time, particularly Dutch paintings, focused on the domestic interior and the material possession within the home. This allowed women to flourish in the artistic realm, but only, according to Dr. Johann van Beverwijck, in the presence of domestic skill. This newfound appreciation for the domestic life varied in interpretation depending on the painter: Vermeer's and Caspar Netscher's paintings of lacemakers emphasized the "intimacy and sensuality of women in repose"; Geertruid Roghman's engravings, by contrast, expressed "the physical labor and utilitarian aspects of cloth production in the Dutch home" (Chadwick 127). Still there was a constant objectification of women in paintings, regardless of the subject matter. Nevertheless, the 17th and 18th centuries saw a wealth of women artists, particularly when it came to needlework and flower paintings (which were considered "feminine" because they pertained to the home). Rachel Ruysch was swamped with commissions for her flower paintings all of her life. To paint flowers "was to symbolize the wealth of the country and was not considered a second-rate activity" (Guerrilla Girls 43). Her flower paintings were tremendously popular in Holland. Ruysch's success inspired other women, who then pursed painting just as she did.

|

| Rachel Ruysch, Still-Life with Boquet of Flowers and Plums, 1704 |

|

| "Plowing in the Nivernais" (1848) |

The history of art and women, furthermore, is the history of women struggling for gender equality, whether they were consciously feminist or not. The lack of women artists in earlier centuries is not due to some deficiency in the female gender, but to the oppressive forces of their male counterparts. As illustrated, women artists are on equal footing with male artists like Michelangelo or Da Vinci—if they are not recognized, it is because of patriarchy, not skill.

Bibliography

Guerrilla Girls. N.p.: Penguin, 1998. Print.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 1990. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment