To summarize 20th century art is a difficult feat. Usually art historical periods can be marked by platitudes; however, there is only one general theme that applies to this century: change. Almost every cultural sector experienced exponential amounts of change in very short periods of time. Unprecedented destruction in World War I gave birth to one of the most remarkable genocides in World War II. It’s no wonder that social justice came to the forefront. In an art historical context, the woman artist could no longer be ignored. This increasing visibility culminated in the Feminist art movement. One artist, Anita Steckel, created work that was a tangible product of several art movements contextualized in a feminist perspective.

|

| "Bush Untitled" |

Anita Steckel formally qualified as a 20th century graphic artist who worked in several mediums. She was born in 1930 to Russian-Jewish parents who immigrated to Brooklyn. Steckel decided to focus on a career as an artist after she graduated from High School of Music & Art in Manhattan (Vitello). She moved to Greenwich village where her perspectives opened considerably. Her youthful adventures included working on a cargo ship and living with Marlon Brando before his iconic rise to fame. To fully summarize the history that influences her work, it’s also necessary to contextualize the artistic attitudes that influenced her development. Anita Steckel was born on the heels of Surrealism, a movement Chadwick qualifies as one that “celebrated the idea of woman and her creativity...passionately” (309). Steckel was undoubtedly exposed to works of contemporary artists, and, in turn, to the “element of erotic violence is so prevalent in the work of male Surrealist artists” (Chadwick 315). To compound the unconventional influences, Steckel also grew up in a time where her contemporary predecessors were challenging the “gendered language that opposed an art of heroic individual struggle to the weakened (i.e., “feminized”) culture of postwar Europe” (Chadwick 320). Steckel absorbed an art education at an extremely unique intersection of deviance from conventions and strengthening female voices.

"Pierced", courtesy of The Brooklyn Museum.

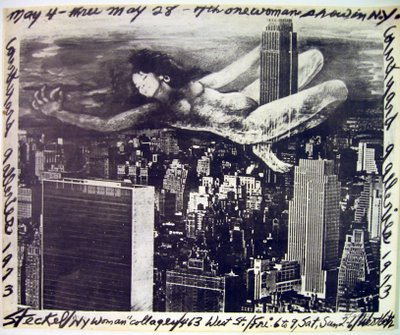

The best way to examine the effects of this idealogical collision upon the artist is by deconstructing her work. The image below, “Poster for 1973 Exhibit”, is a self portrait by Anita Steckel. In the image, the artist personifies herself as a giantess, swinging wildly from the Empire State Building. Text surrounds the image itself in rough, nearly illegible scribbles. Steckel references the iconic imagery of the film King Kong. Her face does not look angry. She smiles with blissful abandon as she quite literally dominates the city. The technical creation of the image is made possible only by the influences of preceding art movements. Cubism legitimized collage as an art form, and the Dadaist designers embraced collage as an entire movement. Steckel collages her head neatly onto the body of the giant woman. The giant woman herself is overlaid on the image of the city; the transparency in the figure’s thigh shows off the photographic manipulation. Narratively, Steckel is completely in line with the doctrines of feminist art. She explores her body, and its power, within a surreal, fantasy world where she rules all. She rejects “the notion of an unchanging female “essence”” (Chadwick 358). Another narrative includes the idea of submission to a phallus. The empire state building is a beautiful structure, but it’s also a huge, obvious phallus. By swinging from the building with wild abandon at a maximized scale, Steckel rejects the notion of male power towering over her. Instead she takes the reigns herself and portrays herself as a giant, empowered woman–just as powerful as the building itself.

|

| "Poster for 1973 Exhibit" |

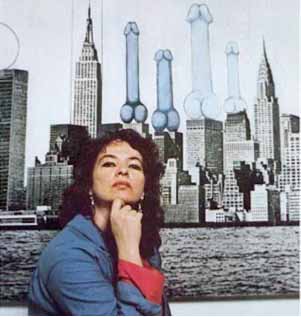

Another telling work is Anita Steckel’s “The Skyline Painting” (1974, below). The work features a photograph of the New York City skyline with penises hovering as an additional part of the buildings itself. The work itself was not included in a 1972 exhibition at the Women's Interart Center in New York, where she was featured with Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro and Faith Ringgold; however, it does characterize a quote for which Steckel is famous. In response to critical uproar and calls for censorship of the exhibition, Steckel replied: “If the erect penis is not wholesome enough to go into museums, it should not be considered wholesome enough to go into women” (Raub). The statement is not of prurient interest. Steckel’s statement reinforces the feminist art doctrine of reclaiming the nude. Nude women are featured almost obsessively in art; yet, the male nude is seen as pornographic or explicit. In an effect to even then clothes-less playing field, feminist artist often chose the male body as a subject of work. Steckel even went on to become cofounder the Fight Censorship group (Vitello). The group believed censorship only served to reinforce established norms, and viewed access to all media, even offensive works, as a good method of challenging the status quo.

|

| The artist, posing with the controversial work "The Skyline Painting. |

Anita Steckel was undoubtedly a radical of her time. Her work is the result of a unique intersection of opportunity and ideology. Women artists in the 20th century took advantage of a completely new level of access to works. The economical strain of World War I and World War II called them into the workforce to replace men. The newfound autonomy created a completely new attitude in the population of working women artists. No longer would the sidelines of pseudonym suit them. They called for acknowledgement of works by women, about women. They challenged the legitimacy of established sexual bias and, in doing so, fought for the right to be called artists, not just women artists. Steckel was swept into this empowering evolution, and created work that both showed her worth as an artist and as an intellectual thinker.

Works Cited:

“Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: Feminist Art Base: Anita Steckel.” The Brooklyn Museum. N.p.. Web. 4 Nov 2013. <http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/feminist_art_base/gallery/anita_steckel.php>.

Raub, Deborah Fineblum. "Of Peonies & Penises: Anita Steckel’s Legacy." Jewish Women's Archive. N.p., 12 Jul 2012. Web. 4 Nov 2013. <http://jwa.org/blog/of-peonies-penises-anita-steckel-s-legacy>.

Vitello, Paul. "Anita Steckel, Artist Who Created Erotic Works, Dies at 82." The New York Times. N.p.. Web. 4 Nov 2013. <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/27/arts/design/anita-steckel-artist-who-created-erotic-works-dies-at-82.html?_r=0>.

Works Cited:

“Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: Feminist Art Base: Anita Steckel.” The Brooklyn Museum. N.p.. Web. 4 Nov 2013. <http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/feminist_art_base/gallery/anita_steckel.php>.

Raub, Deborah Fineblum. "Of Peonies & Penises: Anita Steckel’s Legacy." Jewish Women's Archive. N.p., 12 Jul 2012. Web. 4 Nov 2013. <http://jwa.org/blog/of-peonies-penises-anita-steckel-s-legacy>.

Vitello, Paul. "Anita Steckel, Artist Who Created Erotic Works, Dies at 82." The New York Times. N.p.. Web. 4 Nov 2013. <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/27/arts/design/anita-steckel-artist-who-created-erotic-works-dies-at-82.html?_r=0>.

No comments:

Post a Comment