That same moment, though, also marked the start of our endeavor to free us of that ignorance by acquiring as much knowledge of the lives and achievements of the numerous women who left their mark in the world of art. Now, at the end of the semester, we have been given the same task of naming five women artists and, at this point, it is almost child’s play. It is as if only naming five would be an insult to how much we’ve actually come to learn as a result of this course. But, in order to redeem myself for my inability to answer this question when it was first posed to me, I feel that naming five women artists is a fitting way to bring this course and my transformation from ignorance to cognizance full circle.

The first artist that I will name on my path to redemption is Artemisia Gentileschi. As beautiful as her name sounds, her work portrays the ugly truth about the patriarchal society she was stuck in and the horrible consequences it had on her life. Born in 1593 to Orazio Gentileschi (Guerrilla Girls, 35), Artemisia was, arguably, given the best opportunity to succeed as a woman artist at the time. Her father, Orazio, owned a studio and made a living as an established artist in Italy. Orazio, contrary to most males at the time, allowed his daughter to be educated and helped to cultivate her artistic talent, allowing her to learn and work within his own studio (Guerrilla Girls, 35). It was with the support of her father that Artemisia perfected her style and gained recognition, despite society claiming that Artemisia’s pieces were actually her father’s. Ironically, though, it was her father’s friend, Agostino Tassi, that caused Artemisia to look at life from a drastically different lens and brought about a refinement in her style- making her even more famous, especially to us now in retrospect. Agostino was responsible for the rape of Artemisia and the subsequent psychological torment that brought about the change in her style and subject matter. After the trial and imprisonment of Agostino, Artemisia opened her own studio, became the first female to attend the Accademia Del Disegno, and married a wealthy painter (Guerrilla Girls, 37).

In her studio, Artemisia continued to paint in the style of Caravaggio (deemed Caravaggism) that she had picked up when practicing with her father, a follower of Caravaggio (Chadwick, 105). This is evident in the following paintings portraying similar events that involved Judith, her maidservant, and Holofernes:

|

| Judith Slaying Holofernes, Artemisia Gentileschi 1612-13 |

|

| Judith Beheading Holofernes, Caravaggio 1598-99 |

|

| Judith and Her Maidservant, Artemisia Gentileschi 1613-14 |

|

| Judith and Her Maidservant, Orazio Gentileschi 1611-12 |

Other than the obvious similarities in terms of their style, technique and subject matter, Artemisia did something to set her apart from Caravaggio and her father. She totally changed the context in which she presented the subject matter. She took the innocent looking Judith in Caravaggio’s piece and turned her into someone whose face showed determination and the intent to cut off a man’s head. She took the bewildered and ignorant portrayal of Judith in her father’s piece and figuratively put a head on Judith’s shoulders where she appeared to know what she was doing and was aware of the situation she was in. This blatant change in the presentation of the subject (due in part to being psychologically disturbed as a result of the rape) not only spoke to Artemisia’s skill as a woman artist, it also spoke to her ability to take a piece and give it new meaning. This new meaning was important her in the sense that it challenged the existing notion of how women were ‘supposed to be’ portrayed and gave a voice to women who found themselves in adverse or oppressive situations.

|

| Susanna and The Elders,Artemisia Gentileschi 1610 |

|

| Christine De Pizan in her Study, From The City of Ladies Christine De Pizan 1405 |

One of Pizan’s most notable pieces was called The City of Ladies (Cité des Dames) and, due to the content of its pages, is said to be one the first “feminist” texts accepted in the French canon (Chadwick, 36)- and now most of the world. The City of Ladies is a fictitious scenario where, rather than portraying a patriarchal society that put men at the head of everything, she depicts a community comprised only of women who exist in and govern their own society. The City of Ladies is a commentary that poked fun at the vices of the misogynistic, patriarchy that she found herself living in that put men on a pedestal and made women the pedestal to be stood on. Pizan comes to the defense of women who had, in the past, only been seen for their shortcomings but, through her piece, could now be seen for their accomplishments (Chadwick, 36).

|

| The Bricklayers, From The City of Ladies, Christine De Pizan 1405 |

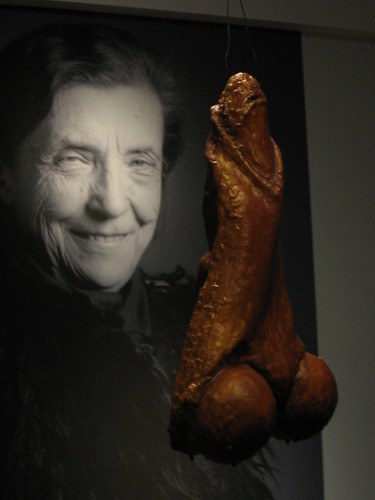

One woman whose name I won’t forget anytime soon is someone I facetiously nicknamed ‘The Erector of Sculptures,’ but her real name is Louise Bourgeois. Born in Paris, France to the owners of an antique tapestry gallery, Louise was raised in the art world and it was in that gallery where she came to love and produce art. After attending numerous prestigious institutions across France, Louise opened her own print store within her father’s gallery where she sold her paintings and engravings- it also happened to be where she met her husband, Robert Goldwater, who convinced her to move to the United States (PBS 2012). Shifting her focus from painting to sculpting, Louise made a name for herself in the art world by being involved in numerous exhibitions as well as teaching art at many high schools and colleges throughout New York. Louise continued to sculpt masterpieces even on her deathbed, making one of her last known pieces only a couple weeks before her death.

|

| Fillette, Louise Bourgeois 1968 |

|

| Seven In Bed, Louise Bourgeois 2001 |

|

| Couple, Louise Bourgeois 2004 |

Another woman I would like to include in my shot at redemption in naming five women artists is Marina Abramovic. Born in 1946 in Yugoslavia, Abramovic is said to have “pioneered the use of performance as a visual art form [where her] body has been both her subject and medium” (SKNY 2013). Growing up, Abramovic had enjoyed painting but slowly began to fall out of love with the two dimensionality of painting as a means of expression. It was then where Abramovic decided that she could use her body as a medium to communicate with the public and she found much more satisfaction in doing so. Using her body, in conjunction with photography, video, and performance, Abramovic has put together a very unique portfolio of art that, once you have seen it, is very hard to forget. One such example is titled Rhythm 0 that she did in 1974 in which she allowed the public to do whatever they wanted to her for six hours with any combination of 72 items that she had spread across a table. The items included a rose, food, perfume, chains, knives, and even a gun. She did this to see how far society would go if they had free reign to do what they wanted and she posed no resistance. She observed that at the end of the performance, no one was able to approach her for fear of what she might do in retaliation but also out of shame for what they had done to her. Another one of her performances was called Imponderabilia where she and her partner, Ulay, stood naked in a doorway and had people pass between them to enter the gallery. This was done to observe what both men and women would do when presented with such a unique situation in terms of who they turned to in order to squeeze through. Abramovic was nothing short of revolutionary in her interpretation of art and ballsy in her presentation of it, helping to open peoples’ eyes to see how far they’d let themselves get carried away.

Ulay & Abramović "Imponderabilia" [1977]

Lastly; the woman who inspired this piece and was, by the same token, inspired by many artists before her is Judy Chicago. Only naming five woman artists is nothing compared to the 39 she paid tribute to in her piece The Dinner Party, but it’s a start. The Dinner Party is the star attraction in the Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum and will continue to draw flocks of people from across the artistic community to see it. The Dinner Party highlights 39 iconic females from throughout history that have been an inspiration to the world, namely other females, and have set precedents that have since made the lives of women across the world a bit easier to live. Among the 39 women in Chicago’s tribute, two have already been mentioned in this piece- Artemisia Gentileschi and Christine De Pizan. The 39 females that Chicago chose to include in her tribute are represented by a tablecloth and a ceramic plate that is modeled after the individuals’ work (like stained glass for Hildegarde of Bingen or cultural masks for Sojourner Truth) as well as a woman’s vulva. The idea that Chicago would make the plates appear as such is a topic of debate and would become the source of its power and popularity in the feminist world.

|

| The Dinner Party, Judy Chicago 1974–79 |

Works Cited

The Guerrilla Girls. Bedside Companion To The History of Western Art. New York: Penguin Books, 1998. Print.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. 4th. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2007. Print.

art21. Louise Bourgeois. PBS, 2012. Web. <http://www.pbs.org/art21/artists/louise-bourgeois>.

The Art Story. Louise Bourgeois. The Art Story Foundation, 2013. Web. <http://www.theartstory.org/artist-bourgeois-louise.htm>.

"Sean Kelly Gallery." Marina Abramović. SKNY, 2013. Web. <http://www.skny.com/artists/marina-abramovi/>.

No comments:

Post a Comment